Japanese Reading Difficulty

9/12 Could be read by 5th grade level student in Japan

Themes

Poetry, Death, Mortality, nature.

Text Type

Poem, Haiku

About Japanese Death Poems

Today we’re having a look at Japanese death poems. Now like the name suggests these are poems that people in Japan have written through the ages just before they die, or on their deathbed, and they’re fascinating little windows into a whole different world across time and space -windows on people reflecting on their lives in their final moments.

These poems have been around since around the 7th century.

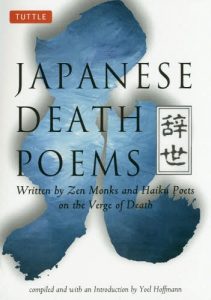

I first came across these through this book Japanese death poems by Yoel Hoffman. It’s a fantastic little compendium of these poems and translations. So I thought I’d go through and introduce some of these but also give my own take. I’ll do some of my own translations, because there’s often quite a few different ways that these things can be done.

A translation of an Instagram post from the artist

智輪

Chi-rin

Died 24 Dec. 1794

The first poem is by a poet called Chirin. All these poets have really fantastic names. 智 Chi means insight or wisdom, which comes from the Sanskrit, I believe, word prajna. So it’s a Buddhist Buddhist concept. 輪 Rin is like a circle, so this is this person’s name is actually a circle of prana insight

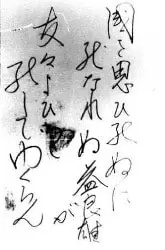

天地に

ちりなき雪の

麓かな

Ametsuchi ni

Chiri naki yuki no

Fumoto kana

Across the sky and land

Not a speck of dust

Behold the snow on the foothills!

Explanation of the poem

あめ in modern Japanese usually means rain but here it’s referring to the sky 天, to the heavens and has a different character to 雨

つち usually literally means dirt, but here it’s got a broader meaning of “land” and then ちりなき

Literally means dust. I think both dust or chiri are very interesting words in either Japanese or English. There’s kind of this association between dust and garbage or rubbish. Probably people that have studied Japanese for a while probably would have come across people saying, you know, get some chiri officer off the floor it’s meaning that it’s dirty & dusty. Even in English we have this word “dustbin”. We don’t put generally don’t put dust in a bin. It’s more like rubbish that we’re putting in there. So there’s this association between things that are dirt or dirty and rubbish.

So ちりなき means ちりがない.

For my translation, I’ve gone with:

Across the sky land land

not a speck of dust and the

But the other interesting thing about ちりなき is that we said that the poet’s name was chirin, so there’s actually a play on words, and this is something you find in a lot of these death poems. Often the poet will take their name and sort of try and work it into the actual poem either through the sound or through the meaning. So there’s this interesting play that they do, looking at the idea of their self and how that idea exists in the world. So chiri naki has a double meaning of no dust, but also no chirin, as in, he himself has disappeared. Or he’s about to disappear.

And then it comes to

雪のふもとかな

Now this word かな is interesting as well.

In modern japanese if you say kana it usually means that you’re not sure about something or you’re wondering about something. So you might say come on 買い物行こうかな, I think I might go down to the shops. Or somebody might say to you そうかな if you’ve said something and now they’re doubting you.

But you find in it’s poetic context it has a slightly different meaning.

Here it’s used as a 切れ字 Kireji.

切る means to cut and 字 is a letter or a word. So these are special words that are put in either to divide up a section or phrase, or at the end to give a sense of finality. “Kana” is usually expressing some kind of wonder, some sense of the numinous. When you think about it, even the modern idea of wondering about things, we wonder at the world, we wonder what’s happening. There is that connection in the same way that we said that ちり and dust and rubbish and garbage have this strange connection. There’s a connection between wondering in a numinous way and in a more prosaic way.

So, the reason I put in “behold” the snow on this foothill is that I was trying to get that sense of wonder. “Behold” I know is a very old sounding English word, but this is a poem from 1794, so I think that’s valid to say, “behold the snow in the foothills”

In Hoffman’s translation he went with:

In the earth and the sky

No grain of dust-

Snow on the foothills

So Hoffman hasn’t worried about putting the “behold” in. The かな gets lost in that translation but really there’s not really any great way of getting around that anyway.

Now, just a way as a way of finding a parallel between this poem and the world of English poetry I was thinking about poets that look at nature, appreciating snow and appreciating the natural world as it is in it in its “suchness”, to use a Buddhist term.

So I was thinking about Robert Frost, because he does a lot of that sort of poetry and he’s got a famous one Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening.

Whose woods these are I think I know.

His house is in the village though;

He will not see me stopping here

To watch his woods fill up with snow.

And then it goes on from there. You get this sense of somebody by themselves in nature just appreciating snow. This makes me think of that famous koan that’s come into popular culture

“If a tree falls in the forest, and no one saw it fall, and no one heard it fall, did it really fall?”

Which is about just appreciating the suchness of things, and the fact that you can’t really explain the nature of reality in words.

Robert Frost also has another poem which refers to both dust and snow as well.

It’s called Dust of Snow:

Dust of Snow

The way a crow

Shook down on me

The dust of snow

From a hemlock tree

Has given my heart

A change of mood

And saved some part

Of a day I had rued.

Japanese poetry books

Japanoscope is a registered affiliate with several online shops and may receive a commission when you click on some of the links within content.

Who is behind this site?

I’m Peter Joseph Head. I lived in Japan for four years as a student at Kyoto City University of the Arts and on working holiday. I have toured the country six times playing music and speak Japanese (JLPT N1).

ピータージョセフヘッドです。3年間京都市立芸大の大学院として、一年間ワーキングホリデーとして日本に住み、6回日本で音楽ツアーをし、日本語能力試験で1級を取得しました。要するに日本好きです。

Podcast: Play in new window | Download